20th June 2025 - 14th July 2025

Preview: Friday 20th June 17:30 onwards, all welcome!

‘Sylvette David Looking Back at Picasso’ Saturday 21st June 11:00 A Talk with the Artist and Lucien Berman. Meet the Artist Saturday 21st June 11:30 – 13:00

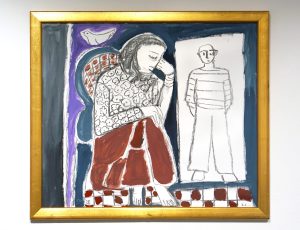

Lydia Corbett (née Sylvette David) is a visionary artist, no less visionary for her failing eyesight, as her subject is focused on inner vision, inner presence. Lydia Corbett’s Retrospective Exhibition at the Penwith Gallery is curated by the artist along with Lucien Berman, Tom Leaper and Jason Lilley.

Lydia Corbett, also known as Sylvette David and known to art lovers all over the world as “The Girl with the Ponytail”, is Pablo Picasso’s last living muse.

—————–

Lydia Corbett née. Sylvette David

The Muse and the Loving Minotaur. Penwith Gallery. 20 June – 14 July 2025.

“I have been particularly struck in this exhibition, by the painting by Sylvette David: Life on a String. It is a sensuous meditation on love and mortality. High modernist art is recalled. There are traces of branches in flower, seen through the background, a shade of red carmine mixed with alizarin. As if to say: what is behind us, is also in front of us. Through the tracery of faint branches, reiterated leaves and flowers, evocations of sensuous otherness, that spring will return to the world. It is the portrait of a woman whose spirit is passing through a harsh winter.

Sylvette David without knowing it at all, is most in touch with compassion when she paints. Through her gift and wanting to hold on to her friend, Sylvette David creates a painting which is a cipher of demurral. The painting is a quiet act of resistance against the suffering her friend was undergoing. The painted figure becomes a protective shell, an outer skin, a tenderness. The artist by finding in recollection and feeling for her friend, through the impact of cancer on her body, the artist embodies her essential beauty.

Great paintings help console the world. They lessen a little our sufferings, by focussing on what matters. Art has truth as a semblance of that which has no semblance. After all, our lives are at best works in progress, we are all variations on the past undergoing transformation.

The figure in the painting is reformed and in transition. The eyebrows are growing back, but painted on for now. The grey-black outline of the figure, and with the scumbled white paint and surface scratch marks, we see the scar traces of metal against skin; we sense a human surface recalled from memory. Sylvette David herself is an old artist who can barely see anymore but still feels the world intensely and remembers. She wants to give support and by painting her friend from memory. She does so in an unfettered compositional purity, making her life timeless, and destined to remain most faithful.

For me, this painting is intense with presence. The woman, the friend, is envisioned by Sylvette, who is full of insight and is herself an almost blind seer. Sylvette David brings them both together; Sylvette David exemplifies the difficult, commonplace suffering that all of us, experience, directly or indirectly. Friendship never grows old. Her friend is essentially the same person whom Sylvette had known for most of her life. I do not find this painting sorrowful, although I know when Sylvette David’s friend had endured extensive radiation and chemotherapy, this painting reminds her, that she still is the same loved person. Sylvette David paints her naked figure to maintain her raw humanity. When Sylvette David paints the lines of the body, what is remarkable is the sheer fluency of her brushwork. Her uncanny ability to inhabit and blend memory with the musée imaginaire of art history. But it was Picasso, after all, who showed Sylvette how to reconcile the ill-matched threads of a life, and weave them gratefully into a single canvas. He is still the last companion of her artistic being. She has learnt to hold on to her inner vision, and stretch herself beyond what limits her even now she is losing her sight – to bind image to gesture. * In Sylvette David’s late oil paintings and acrylics, on show in this exhibition, often charcoal outlines are sketched in, then light and shade, and colour becomes form. The surface texture of any overpainting becomes ‘impasted’ and overlaid by a sequence of reworkings. The French word for reworking repentir carries with it a trace of atonement and almost regret. But the process of transformation necessitates sacrifice to reach the final state. This is an oscillation between light and form, and form and memory. The freedom to alter, to erase and paint over and to experiment is the raison-d’être for the painter’s existence. Many of Sylvette David’s recent oil paintings are studies in immanence.” Lucien Berman Sylvette David / Lydia Corbett, Ceramics, Painter and Sculptor in Clay by Lucien Berman Available at the Penwith Gallery Bookshop. Lydia Corbett née. Sylvette David The Muse and the Loving Minotaur, Penwith Gallery. 20 June -14 July 2025 Picasso and Sylvette David, in Vallauris, 1954. Photo Credit. Tobias Jellinek/ Sylvette David archive. “Picasso, Sylvette and La Femme à la Clé (The Woman with the Key) is a painting the artist finds close to her heart. Sylvette David is now ninety years old. The painting relates to the day that Sylvette discovered Picasso had made a life size sculpture of herself. The bronze sculpture, he had got cast whilst he was away, and they had not seen each other for some months. In a studio at the Madoura workshop in Vallauris, in the South of France, The Woman with the Key was also conceived in its original assemblage, in Sylvette’s absence. It was made from fragments of firebricks, used to line the kiln oven, a long-curved fireclay prop, known as a gazelle, which formed her body, and created her neck, and her arms and legs and handbag from hollow fireclay stilts. These parts originally were used to help space objects in the kiln. Her shoulders and breasts are a damaged rooftile. Preparatory sketches show that Picasso had envisaged using loops of bronze to capture how he recalled that Sylvette used to swing her clutch bag on her wrist as she walked. Sylvette David had spent six months in the mind and company of Pablo Picasso. She was nineteen. He was seventy-three. He transformed her life, both inwardly and outwardly. He showed her nothing but respect and kindness, and tenderness. Then when he first exhibited some of the paintings, the international press descended on the little town of Vallauris. The Epoch Sylvette, was how Paris Match described this new Picasso period. After Sylvette had stopped visiting him, Picasso had to crawl about on his hands and knees to make this high priestess of the kiln. But it is much more than a reliquary. When cast in bronze, it took on a life of its own, and throughout Sylvette’s life it has become something of a protective spirit, a guardian angel. This fascinating exhibition at the Penwith Gallery is showing a broad range of her recent works, including this painting, which reminded me of Charlotte Salomon’s autographic paintings done as vivid gouache self-portraits, in Life or Theatre, made when the German Jewish woman was in her twenties between 1940 and 1942, in a burst of energy before she was deported to Auschwitz in 1943. Sylvette David with advanced retinal degeneration also paints for her life to be lived to the full and be remembered. In this late period of her art, what is striking is the wide range of Sylvette David’s works and their emotional and expressive depth. Sylvette, as a visionary, spiritual, artist, was best known for her watercolours: with their delicacy, translucency, and that pared-down balance between form and chaos, they emanate from the English tradition of David Jones, Cecil Collins, and Samuel Palmer. But now it is her Late works on board in oils and acrylics, that have come into their own. Of her recent oils, are gesturalist works recalling artists as distinct as William Scott, and Willem de Kooning’s late paintings, in their existential import. Sylvette David has painted some small charcoals on boards which are cryptic self-portraits of her inner life. Sylvette David is an artist who creates because she has to create. In all her work there is a sincerity of intent. Sylvette David’s immediacy is immersive and binding. This is particularly so for those recent paintings which manifest the trauma and fragmentation wrought on her vision; not by uncontrolled apprehension – but by time itself, and the struggle for visual coherence. Failing eyesight has not hindered, it has strengthened Sylvette David’s inner vision. * Sylvette’s many months spent with Picasso gave her by his example, the confidence to paint throughout her life. What Sylvette learnt from her time in his studio was to understand how to alter everything, to believe in spontaneity and have the freedom to do as she pleases, to experiment with life through the transformations of making. In the self-portraits which return Picasso’s Vallauris studio of 1954, Sylvette David is not wearing away at recurring memories, she is finding, in each new painting, a lost reality of the place, through her act of complicity with her younger self. She is finding something essential – in the process of painting which returns, with an unpreparedness as powerful as an involuntary memory. Painting herself, Picasso, and the place where they spent so much time together, becomes a cue and a clue, a link back to that past, without any conscious effort on her part. She does so with a freshness and vitality. Le Fournas, in Vallauris in the South of France, was where she would meet Picasso. Sylvette was a nineteen-year-old girl, Le Fournas was a former perfume factory where Jasmin and orange blossom essences had been distilled. In a sense Picasso continued with Sylvette the art of distillation, of defining and trapping essences. Picasso said: “All I have ever made was made for the present, and with the hope that it will always remain in the present”[1] Picasso now has been dead for over 50 years, but the works he painted of Sylvette David, and the sculptures he created are timeless. And each year that passes, the distance between them gets closer. Many of the best-known portraits of Sylvette by Picasso are in profile, now she is returning his gaze as we see in the exhibition at the Penwith. Sylvette David is seeing too, what he could not see of her. When Sylvette David returns in her art to Picasso and Vallauris, she is painting through the symbolic and the real. Only this deep immersion and will to be herself has led to her creative independence. The dialogue is no longer attached to particular moments of being but their essences. It was Picasso who taught Sylvette that the line does not have to be the edge, nor the outline of an object – it can be a palimpsest between the subject or object and the space it inhabits. For some artists the problems of old age relate to physical decline. Poussin’s hands became shaky, Titian’s eyesight faded. For others, psychological symptoms affect the ages of senescence. Art has its life cycles too – back in the day, for even the Italian old masters of the 16th century – the late Mannerist ‘modernists’ – were spoken of, at the time as dilavata, “washed-out” long before they reached pension-age. Although there were exceptions – many others died young and there was always Michelangelo, the hypochondriac young fogy; and the multiphobic Pontormo. Still, Picasso, the great survivor of the 20th century, had to follow the example of Titian as a shrewd mark-maker and racketeer of old age, and the spirit of Tintoretto who at the age of 82 knocked up an extraordinary Paradise in the Doge’s Palace. For many months in 1954, Picasso was not just looking back, he was looking forward. Picasso loved Sylvette with the gift of artistic prophesy. Once Picasso possessed her with his mirada fuerte, his Andalusian gaze. It seems that Picasso has kept Sylvette young all these years. Now in her nineties, she can still feel his blue-veined hand reaching into hers and his silent presence steadies her frail wrist as she paints.” -Lucien Berman Sylvette David / Lydia Corbett, Ceramics, Painter and Sculptor in Clay by Lucien Berman available at the Penwith Gallery Bookshop. [1] Pablo Picasso, Dore Ashton, ed., Picasso on Art: A Selection of Views. (New York) 1972, p.5.